The Proteus Effect and How Your Avatar Shapes You, Including the Impact of Digital Identities on Behavior

The proteus effect isn’t a new topic in our discussions about avatars. There are several articles worth revisiting, such as the origins of avatars from the Marvel series “Moon Knight”—an avatar that serves as an ancient deity’s agent on Earth and a virtual embodiment in the metaverse, acting as a crucial intermediary across dimensions (divine and human; physical and digital). Another recent series on virtual humans explores the history and evolution of virtual idols and VTubers, examining the two-way relationship between virtual and real worlds—we create avatars in the virtual world and can also breathe life into them (soul to skin), bringing them into our reality.

With the rapid development of AI, we are in the final sprint towards AGI, making virtual avatars and non-player characters (NPCs) even more intriguing. Additionally, the recent launch of VIVERSE Create v1.0 introduces an avatar system based on the VRM format, featuring styles from American cartoons, Japanese anime, and photorealistic designs. This not only brings us back to the nostalgic joy of creating avatars but also makes me reflect on the relationship between avatars and myself.

What is the Proteus Effect?

Psychologists have long been interested in virtual avatars. Since the launch of “Lineage” in 1998 and “World of Warcraft” in 2004, the advent of the internet has completely transformed video games, especially MMORPGs. Gamers can freely choose their gender, race, and profession, and “role-play” their avatars into other worlds, meeting people from around the globe. This groundbreaking phenomenon, which involves many aspects of self-identity, naturally piqued the curiosity of psychologists.

In 2007, Stanford University scholars Nick Yee and Jeremy Bailenson initiated the study of virtual avatars with a paper published in the “Human Communication Research” journal titled “The Proteus effect: The Effect of Transformed Self-Representation on Behavior.” This introduced the “Proteus Effect,” providing a framework for understanding how virtual avatars can influence our behavior.

Proteus, a sea god in Greek mythology (sometimes said to be Poseidon’s eldest son), possessed two main abilities—shapeshifting (changing forms at will) and prophecy (revealing the future only to those who could see through his true identity). The term Proteus has also evolved into the adjective “protean,” which connotes signifies flexibility, versatility, and adaptability.

The “Proteus Effect” suggests that the appearance of virtual avatars used in virtual worlds not only affects users’ behaviors within those worlds but also impacts their real-world behaviors, cognition, and emotional states. In plain terms, when you change your virtual avatar, your behavior and thoughts might also change. Thus, named after this elusive sea god, the “Proteus Effect” represents human adaptability and fluidity through virtual avatars.

Two years later, the scholars continued their 2007 research and published a paper titled “The Proteus effect: Implications of Transformed Digital Self-Representation on Online and Offline Behavior.” The 2007 study primarily examined whether the height of a virtual avatar would affect in-game behavior. The 2009 study, using VR, allowed participants to play as various races from World of Warcraft, such as the shorter Gnomes and taller Night Elves, and found that height and race significantly influenced their behaviors.

For instance, participants playing as taller avatars tended to choose more advantageous but ultimately unfair offers during negotiations, and they were also more likely to reject the split. Moreover, participants who played as taller avatars maintained a more assertive personality not only in the virtual environment but also in real life, suggesting that users adjust their behaviors to match the expectations and traits of their avatars.

How Does the Proteus Effect Work? Six Psychological Hypotheses

That idea that virtual avatars influence our behavior, both online and offline, has been proven by experiments, but how do we explain the mechanisms behind the Proteus effect? Nick Yee and Jeremy Bailenson, who proposed the Proteus effect, adopted two explanatory hypotheses: “self-perception” and “deindividuation.”

- Self-Perception: This is the most commonly cited hypothesis to explain the Proteus effect. Users infer the attitudes they should have based on the appearance of their virtual avatars, such as assuming that being taller usually means more confidence, thus displaying confidence during negotiations.

- Deindividuation: Refers to the immersive nature and anonymity of virtual environments, making it easier for users to express their opinions or engage in behaviors they wouldn’t normally exhibit in real life.

These two hypotheses provide explanations from both active and passive perspectives. Subsequently, other scholars have proposed additional psychological assumptions to refine the explanation of the Proteus effect. According to a 2024 review by Anna Martin Coesel, Beatrice Biancardi, and Stéphanie Buisine published in “Frontiers in Psychology”, there are four more hypotheses: - Cognitive Dissonance: This supplements the self-perception theory. It refers to the tendency of people to change their attitudes or behaviors to reduce discomfort when their beliefs, attitudes, and values conflict. Applied to the Proteus effect, users adopt attitudes or behaviors consistent with their avatars’ appearances to avoid the psychological stress caused by cognitive dissonance.

- Priming Effects: Similar to self-perception, but priming effects emphasize “unconscious associations” that stimulate certain behaviors, such as activating a sense of professionalism and authority if the virtual avatar is dressed in a doctor’s robe.

- Embodiment: This refers to the virtual avatar as an extension of the user’s body. For example, using an avatar skilled in sports might make the user feel more confident, encouraging them to try new sports in real life.

- Perspective-taking: Simply put, this is about putting oneself in someone else’s shoes. For instance, playing as an avatar from a minority group might reduce prejudice and increase empathy.

It’s important to note that these six hypotheses interact with each other, and no single theory can fully explain the Proteus effect.

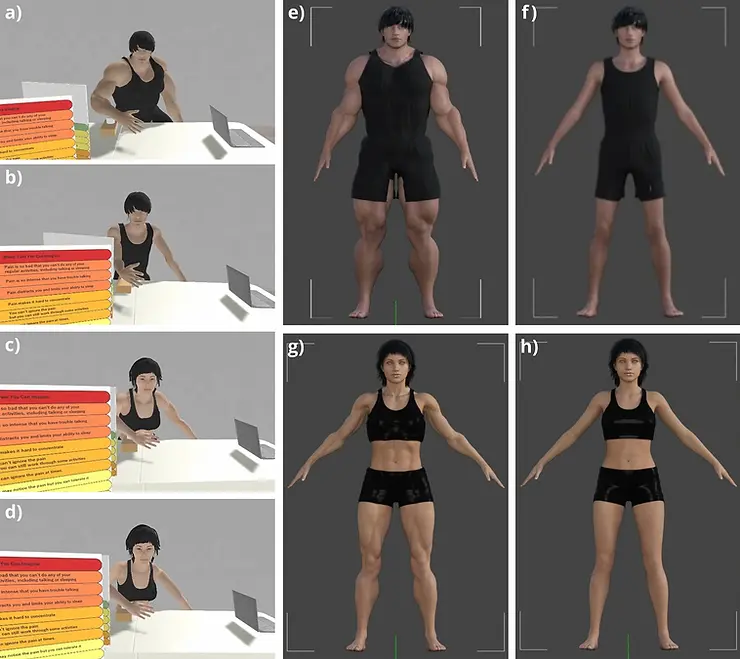

Recent studies have found that previous emphasis on the immersive nature of VR aiding in pain relief is not comprehensive enough. A paper published in “Scientific Reports” incorporated the “Proteus Effect” into its experiments. The results showed that using virtual avatars effectively reduced pain perception regardless of gender. Interestingly, when male participants used more muscular avatars, their pain perception decreased by 15.982%, and their pain tolerance significantly increased, but there was no significant difference for female participants, whether they used stronger or average avatars.

The paper speculates that this is due to gender stereotypes, where masculinity and strength are positively correlated with pain tolerance. This reminds me of a German research study that used heavier avatars to help patients with anorexia, as well as Oxford University’s VR study on the association between delusional disorder and self-esteem—both of which demonstrated the effectiveness of the Proteus effect.

While it’s often said that on the internet, nobody knows you’re a dog, in reality, that canine nature is also ingrained in your being and hard to escape. The impact of virtual avatars on our daily lives is no less significant than the social roles of being parents or children. This fusion of the virtual and real worlds will only become more pronounced in the future.

Perhaps this is why VIVERSE’s Avatar embraces such diverse styles—virtual avatars not only represent the original self but also embody many unrealized possibilities. The physical you and the digital you are like pieces of similar yet subtly different images that, when assembled, form a complete self.