Stanford VR Research at 30: 5 Key Insights into Avatars, Full-Body Tracking, and Immersion

Original Author: 庭庭迴旋踢 Edited by: VIVERSE Team

Stanford VR research has played a pivotal role in shaping the field of virtual reality. For 30 years, Stanford’s Virtual Human Interaction Lab (VHIL) has studied how people behave and communicate in immersive digital spaces. To celebrate this milestone, the VHIL team has released a retrospective collection featuring five major insights. These cover avatars, full-body tracking, behavioral shifts, and more, summarizing decades of research. These findings not only reveal where VR has been but also offer guidance on where it might go next.

5 Key Insights After 30 Years of VR Research.

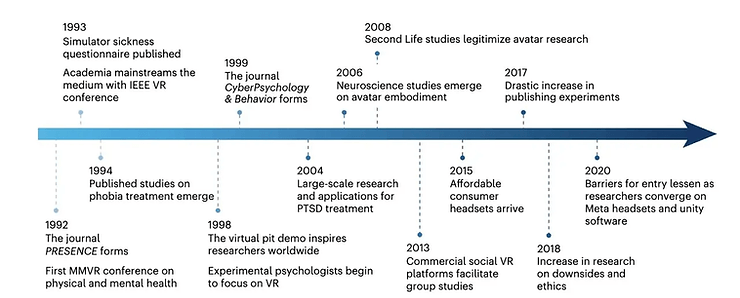

VR is often linked to gaming, but it’s also a powerful tool for psychological and behavioral research. In 1992, PRESENCE, a full academic journal dedicated to VR, was launched. Back then, researchers were already studying “presence,” VR motion sickness, and how VR might help people overcome specific phobias.

However, recent statistics show that more than half of all VR-related experimental studies have been published since 2018. This shows that as VR devices improve, studies have also expanded. Early studies focused on presence and sensory perception. Research has since expanded into avatars, social behavior, education, and more.

With that in mind, let’s explore five key findings from a Stanford-led team’s 30 years of VR research.

1. More Immersion Isn’t Always Better.

In VR, “presence” or immersion refers to feeling truly located in the virtual environment. This is widely known as VR’s most compelling trait, as it is what sets VR apart from traditional media. But studies have actually shown that presence isn’t always beneficial. The key is how and where it’s applied.

Presence offers the greatest benefits in fields like training and therapy. Examples include simulated surgeries, military drills, or phobia treatments like airport reconstructions for flight anxiety.

For instance, HTC VIVE and V-Armed work with law enforcement to build VR training for de-escalation and tactical response. In pain management, VR can redirect attention or create out-of-body illusions to reduce perceived pain.

However, in communication or entertainment, the results vary. While popular VR titles like VRChat and Gorilla Tag have spiked in popularity, social VR has yet to become mainstream.

Researchers believe presence requires full attention, unlike social media, which people often consume while multitasking.

So yes, VR delivers a strong presence, but using it effectively requires matching it to the right context. If you’re designing a VR experience, ask whether full immersion adds value or causes fatigue and distraction.

2. Avatars Don’t Just Shape Looks, They Influence Behavior.

In VR, we normally start by “putting on” an avatar, similar to how we put on clothes in the morning. Research has shown that these appearances aren’t just cosmetic—they subtly shape our attitudes, behaviors, and decision-making.

One finding, proposed by Jeremy Bailenson and Nick Yee, is called the Proteus Effect. This phenomenon is known as the Proteus Effect. It shows people often change their behavior based on their avatar’s appearance. For example, taller avatars lead to more confident negotiation behavior, while frail avatars might cause users to act more cautiously.

But it’s not just about appearance. When virtual limbs mirror real movement, it can trigger a sense of “body ownership.” Research shows this sensation isn’t just visual but affects memory and self-perception (even without haptic feedback). This effect helps users feel that their virtual body is truly part of themselves.

Over time, these subtle influences accumulate, impacting social behavior, emotional regulation, and even bias formation. Researchers caution that even default avatars or movement systems can unconsciously affect outcomes in VR experiments, whether studied directly or not.

Avatar choices aren’t just stylistic choices, but actually gradually shape how we see ourselves and interact with others.

3. VR Education Isn’t Suitable for All Learning.

Using VR applications for education isn’t new, spanning flight simulations, medical training, museum tours, and language learning. But VR doesn’t work in every single aspect of education. When it comes to abstract ideas or complex logic, immersive environments can backfire.

VR excels at tasks involving hands-on practice. Procedural learning tasks, like practicing surgical steps or factory workflows in VR, help users retain knowledge and apply it in real life. Simulating fire emergencies with VR for firefighting has been an amazing part of VR education, thanks to FLAIM Systems.

However, teaching abstract concepts like theories, mathematical formulas, or historical narratives can lead to cognitive overload. Too much sensory input diverts mental energy toward processing the environment instead of understanding content. This is especially challenging for younger learners or those with less-developed learning strategies.

Interestingly, many failed VR education cases come from simply porting 2D materials into VR, like playing videos in a virtual classroom or having avatars read out loud. It may seem modern, but it often performs worse than traditional methods.

4. Full-Body Tracking Revolutionizes VR, but There’s a Catch.

Full-body tracking is absolutely amazing. Every head turn, wave, step, and even eye movement is brought into VR in real time. When it comes to immersion, there honestly isn’t anything better (for now).

For researchers, full-body tracking is a goldmine of user behavior. Every limb or tracking point is a metric that can be analyzed. For example, hand motion paths, gaze shifts, or posture stability can indicate attention levels, stress, or even predict sensory sensitivities or ADHD. In multi-user experiences, physical cues help assess social rhythms, interpersonal space, and nonverbal communication.

But are there privacy concerns? Studies show that just five minutes of head and hand motion data can identify individuals with over 90% accuracy.

So, while VR with full-body tracking is just pure fun, we must also recognize that it may be a privacy risk.

5. People Tend to Misjudge Distance in VR.

VR takes some time getting used to. When navigating through virtual reality, users tend to underestimate how far things are when performing everyday actions like grabbing objects, walking, and jumping.

Though it seems minor, distance distortion can degrade the whole interaction quality of VR. It reduces the accuracy of precision movements like throwing or grabbing and affects the timing and comfort when interacting with other users.

Surprisingly, this issue persists even in passthrough mode, where users view the real world via headset cameras. Just because something ‘looks real’ doesn’t mean we are accurately perceiving it.

These issues are still being studied, but possible causes include limited field of view, weak depth cues, compensating movements due to headset weight, or even how shadows are rendered.

Developers are actively working on fixes like using depth-sensing cameras, adjusting avatar eye height, or tweaking ground shadows and field of view.

What’s Next for VR?

These five findings won’t solve every challenge in VR, but they offer widely agreed-upon insights for how the world interacts with virtual reality. After thirty years, VR isn’t just a type of entertainment, but a lens for observing human behavior, placing users in new roles and environments. Whether we use this technology to expand our understanding of the real world is up to us.